Source: The Bhagavad Gita in Pictures

During the first couple of weeks of Trump’s chaotic presidency, I’ve found myself regularly doing Warrior Poses in my home yoga practice. Warrior poses are strong poses, with clear and firm lines of energy and highly engaged feet, leg, core, shoulder, and arm muscles. While doing these poses, I’ve spontaneously imagined myself on several occasions as Arjuna, the famed archer and mighty warrior in the Bhagavad Gita, probably the most vivid, revered, and compelling narrative expression of yoga philosophy among all the ancient texts.

I’ve been drawn to Arjuna’s story and his dialogue with his trusted charioteer, Krishna, because they exemplify a kind of strong, devoted, and heart-centered leadership so tragically lacking in the Trump regime but which I long to see and be inspired by in our national leaders. And imagining myself as Arjuna helps me to envision ways I can constructively respond, even in small ways, to Trump’s assault on our democracy and on the institutions and people that make it work.

I first read the Bhagavad Gita, which is sometimes referred to simply as the Gita, about 15 years ago in my yoga teacher education program. I’ve returned to it several times since then, but never with as strong a sense of urgency and political and cultural relevance as I’ve been feeling lately.

This essay is a chance for me to bring forth into our disturbing present the hopeful qualities of leadership that the Gita offered two thousand years ago. I want to contrast the light of the Gita with the darkness of Trump’s domination. The story of Arjuna and Krishna shows that the possibility for good leadership has long been within our human consciousness. I hope that you, as a reader, also find inspiration in the Gita’s message.

Let me start with a summary of the Gita for those who are not familiar with it.

The Bhagavad Gita at a Glance

The Bhagavad Gita is a 700-verse Hindu scripture, composed in Sanskrit probably between the fifth century BCE and the second century CE. It’s widely considered to be the most loved ancient text in Indian philosophy and spirituality.

There are many English translations of the Gita, but the one I refer to in this article is the one I studied in my teacher education program, by Graham Schweig (HarperOne, 2007) and that I’ve returned to periodically over the years.

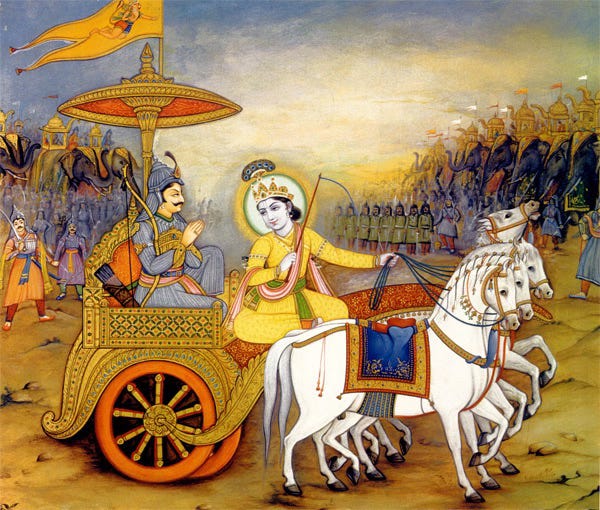

The heart of the Gita is an extended dialogue between Arjuna, a prince and a general, and Krishna, his wise charioteer, who is secretly a manifestation of divinity. The conversation between the two main characters takes place on the battlefield of Kurukshetra just before a war of epic proportions is about to begin.

At the start of the story, Arjuna faces a wrenching moral dilemma that fills him with dread: to lead his troops into battle and risk killing his own relatives, friends, and teachers who are on the opposing side or to forsake his command, turn away from his historic destiny, and fail to protect the innocent. The dialogue between Arjuna and Krishna is about Arjuna’s confrontation with this dilemma and the counsel Krishna provides Arjuna to help him find his way through it.

While the story is set in a battlefield and concerns a dilemma of warfare, the book is not really about fighting enemies in the world. At a deeper level, it’s about Arjuna’s listening to God’s voice to help him openly face and resolve conflicts within himself. Bhagavad means “the Beloved Lord,” and Gita means “song.” The subtitle Schweig gave to the text, “The Beloved Lord’s Secret Love Song,” is an important clue about its central meaning. In its most essential form, the book is about a song from a loving God’s heart that beckons a human soul to seek refuge in divine arms and find strength, purpose, and courage in the divine embrace.

Leadership as a Sacred Duty vs. a Vengeful Conquest

To me, the most basic contrast between the leadership model of the Gita and the leadership embodied by Trump concerns purpose. While Arjuna comes to understand that his purpose is to fulfill his sacred duty to fight a just battle and protect his people, Trump’s purpose seems to be to conquer his perceived enemies, whether they be immigrants, members of the so-called deep state, Democrats, journalists, or countries or territories that are not falling into line. Whereas Arjuna seeks to serve the greater good, Trump’s drive is to dominate.

While Trump’s power plays seem obvious, Arjuna’s more positive motivations deserve more discussion. One place to start is the very first phrase in the opening verse of the Gita: “On the field of dharma.” In a literal sense, the field is the battlefield, where Arjuna is struggling with doubt and despair about the prospect of waging war. But in the context of the Gita, the field of dharma is a symbolic field, where Arjuna comes to discern and dedicate himself to his dharma.

From what I’ve gathered, the word dharma can have varying meanings depending on the culture and context in which it is being used. In the Buddhist tradition, dharma seems most often to refer to the Buddha’s teachings about the path to Enlightenment and liberation from suffering. But in the yoga tradition, dharma is fundamentally about the soul’s calling, and in the case of Arjuna, his calling is his sacred duty to fight a just war.

What makes Arjuna’s dharma sacred is that it is infused with the divine, an “eternally indestructible” presence that “dwells within the body of everyone” (Chapter 2, verse 30). Arjuna’s dharma is his unique path but one that springs from his bond with the divine and the moral order inherent in the universe. As Schweig wrote in his commentary about the meaning of dharma in the Gita, the dharma is “a state of righteousness, a personal calling to goodness, cosmic harmony, sound ethical law, or justice.”

To be sure, Trump also claims a special connection with the divine. According to his recounting, his life was spared by God following two assassination attempts to save America from the alleged damage to the nation inflicted by Presidents Obama and Biden and all of their ilk. But by no reasonable standard can it be said that Trump as a person or as a leader is an emissary of God, however one conceives of God. Trump is about the raw exercise of power. God is not involved.

Love-fueled vs. Hate-fueled Leadership

For Arjuna, his sacred connection to the divine is not only a source of purpose. It’s also the ultimate source of love. The Beloved Lord’s infinite love for Arjuna, which Krishna makes palpable and real, opens Arjuna’s heart and moves him to a state of full-hearted devotion to the divine and to his divinely guided dharma. Arjuna’s dharma becomes not merely a duty but an act of loving service.

Love as an intimate union with the Beloved Lord is at the core of Arjuna’s leadership. The quality and mutuality of this union is expressed in these verses from Chapter Nine, which is one of my favorite chapters. Krishna, channeling the Beloved Lord, says:

“I am …the innermost heart….

I radiate warmth…

I am the same toward all beings…

Yet those who,

With an offering of love

Offer their love to me–

And They are in me an

And I am also in them.”

Once again, I want to quote Schweig because his words about the centrality of love in the Gita are eloquent:

“The Gītā’s ultimate teaching—its response to the question of how souls should act in this world—is that souls should at all times and in every circumstance act out of love. By hearing Krishna’s call to love, Arjuna discovers a more elevated state of consciousness, then an inner state of transcendence, and finally, a state of eternal freedom in which his heart can fully love God and, consequently, all beings. From this newfound fortitude and love, Arjuna is prepared to act with full-heartedness.”

Granted, the Gita is a myth, and the kind of loving, devotional leadership it talks about is not easy to translate into the turbulent and messy world of contemporary politics. But Trump makes no effort at all to ground his actions in love. Instead, his rants and retribution seem powered by hate.

Trump did suggest that the January 6th insurrection at the Capitol, which he egged on, was a “love fest.” And then, as an act of reciprocity, he pardoned or commuted the sentences of even the most violent offenders. But if this is love, love has no meaning.

Further, Trump seems to hate immigrants, or at least hates those who come from “shithole countries” or who can’t help him sustain or enlarge his power, as his South African immigrant partner in power, Elon Musk, is doing.

Trump also seems to hate the whole movement toward “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” which has its roots in the Civil Rights era. To me, DEI, despite some missteps and excesses along the path, has served a noble purpose: to help us build a more decent, humane, and just society, one that might perhaps some day become the “beloved community” for people of all backgrounds and identities that Dr. King championed. DEI also serves as an adjunct support to our humanitarian efforts around the world.

When Trump blamed the horrible collision of the Black Hawk helicopter and the American Airlines jet outside of Reagan Airport in D.C. on DEI, I couldn’t help feeling this was borne from hate (and from racism, along with a relentless need to find a scapegoat for every ill that befalls us as Americans).

Leadership that Acknowledges Doubt vs. Leadership that Denies it

We might think of ancient yogis, of which Arjuna could be considered one archetype, as withdrawing from the world in silence, austerity, and meditative calmness, perhaps in a cave. But Arjuna lived in the world of action. His dharma was to be a great and just general and to fight with all his heart. The battle that Arjuna was facing did not allow him to be withdrawn and quietly calm.

The Gita makes clear that Arjuna struggled deeply with the choice thrust upon him by his role in his family and among his people. As he contemplated killing his relatives, he was tormented by sorrow and “overwhelmed by compassion,” with “troubled eyes…full of tears.” (Chapter 2, first verse). The harm he would inflict in battle tore at his soul:

“My limbs are sinking down

And my mouth has

become very dry.

Also, my body trembles

And the hairs of

My limbs stand on end.

My bow, Gandiva,

Falls from my hand

And even my skin is burning.

I also am unable to stand steadily and

My mind seems to be reeling (Chapter one, verses 28-31).

As the Gita unfolds and Krishna offers his indispensable and wise advice, Arjuna’s torment eases. But the ease does not come until he faces his painful self-doubt and uncertainty. The price Arjuna pays for having an open heart is to deeply feel his inner struggles and his compassion for those he might harm.

In showing that he was a whole person, one who could feel and express his own vulnerability, Arjuna modeled the kind of authentic leadership that inspires trust.

In contrast, I have never known Trump to admit to any vulnerability. He always appears wrapped in his own certainty. He never admits a fault or a mistake. He shows no inner awareness and no sense of inner accountability. He doesn’t seem to be a whole person. It’s hard to trust a leader who is in such denial.

Leadership that Does What’s Right vs. Leadership that’s Merely Transactional

One of the themes in the Gita is about the importance of doing what’s right regardless of any anticipated benefits to oneself. Discerning what’s right might not be immediately apparent. It might involve wrestling with a dilemma. But what determines the right course of action is an ever-clearer understanding of one’s dharma, as it flows from the soul’s union with the divine, and of the meaning of dharma in the present moment. A calculation of self gain should not enter into a leader’s decision-making.

Krishna makes the point in various ways and in various places in the Gita that when one seeks refuge in the Beloved Lord and keeps their attention on dharma, one can be free from an “attachment” to action, and in this freedom lies the path to a better world. “Attachment” in this context refers not so much to action itself as with the “fruits of action.” Krishna is saying that there is an intrinsic morality to living one’s dharma in harmony with the divine “without longings” and without a sense of “mine.” Free from selfish desire, a leader’s action will advance the common good. As Krishna instructs Arjuna:

“As the ignorant act,

attached to action…

So the wise should act

without attachment,

desiring to act for

the welfare of the world” (Chapter three, verse 25).

The selfless, morally grounded leadership that Arjuna represents is the antithesis of Trump’s leadership. Even when Trump claims that his proposals spring from a desire to serve a higher purpose, more often than not, they seem to be nothing more than a way of asserting his dominance, or his need to dominate projected upon America and the world. Do we really need to take over Greenland to advance our collective welfare?

Consider his idea that the people of Gaza will be happier if they move to Egypt and Jordan and that Gaza will be better off if the US can develop it as prime real estate. This sounds like Trump the business deal-maker, out to enlarge the holdings of the United States, enrich his wealthy friends and corporate supporters, and ultimately make money for Trump and his family. Trump’s defining leadership principle, if one can call it a principle, seems to be, “Be bigger, tougher, and more aggressive than the other guy and always play to win.” Considerations of the common good never seem to enter his mind.

I’m appalled by Trump’s boundlessly egoistic leadership. But I find inspiration in the moral and devotional ideal of leadership that the Gita so richly develops. This ideal may be too pure to realize fully in the complex world we live in, but it offers a worthy vision to strive for. We don’t have to be Hindus or Yogis to appreciate leadership as a sacred calling, an embodiment of loving service, and a commitment to cultivating inner awareness and doing what’s right even when this doesn’t help us personally. The Gita’s portrait of leadership is stirring me to deepen my engagement in the political arena. Might this vision stir you?

As always, I’d love to receive and respond to any comments you might have. What do the themes explored in this piece evoke for you? Please feel encouraged to use the comments option that Substack provides with this post.

Dear Brother,

Thank you for another informative and thought-provoking article! I loved learning about the Gita and Arjuna’s struggles.

I can relate to this in my own way—not as a warrior or a political leader, but as an entrepreneur, a founder, and a CEO.

Regarding your note that "a calculation of self-gain should not enter into a leader’s decision-making," I wonder: can a good leader incorporate personal and organizational benefits into their decision-making while still striving to do good for the world? For example, if there is a decision that benefits the world in some sense but is not advantageous for my firm and its 30 employees, does it make sense to reconsider an approach that aims to benefit both my firm and the world?

This is so well done Glen, and quite interesting. One of my favorite lines: “But if this is love, love has no meaning.” Thank you!